|

Slipform Stone Masonry

By Danielle N. Gruber. Forward by Thomas J. Elpel

In my article The Art of Slipforming in the January 1997 issue of The Mother Earth News, I proposed a new method of slipform stone masonry, where the entire house could be framed with polystyrene beadboard insulation panels before beginning any stone masonry. The beadboard panels would serve as forms inside the wall and the stone masonry would be slipformed up the outside. That way it would be easier to build straight, plumb walls with less labor and fewer slipforms. The beadboard panels would also eliminate expensive wood framing on the inside of the walls while maximizing energy efficiency by eliminating thermal gaps through the framing. At least that was the theory. I hadn't actually tried it myself.

The article in The Mother Earth News was my first step in writing the book Living Homes: Stone Masonry, Log, and Strawbale Construction, which took another four years and three interim comb-bound draft editions before it was finished.

The article in The Mother Earth News was my first step in writing the book Living Homes: Stone Masonry, Log, and Strawbale Construction, which took another four years and three interim comb-bound draft editions before it was finished.

Early in the process of writing the book I received a phone call from Dani Gruber in western Colorado. She read the article in Mother and wanted to test out the new method of slipforming I had proposed. Dani asked a few questions, which I answered to the best of my ability. I sent her draft copies of my book to help guide her work. As far as I know, the Gruber house is the first structure ever built with the technique, and I'm thrilled (and relieved) that it actually worked!

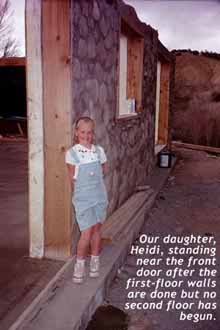

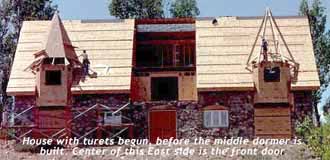

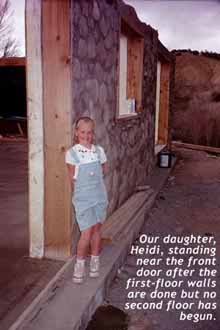

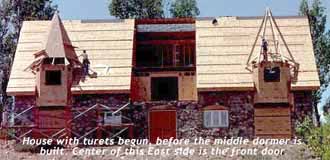

Part way through the process Dani wrote me the following e-mail letter with attached pictures, which she gave me permission to post here. Later she wrote a more extensive article about the process, which is included after the letter. As you can see from the photos, Dani was a very inspired builder. Their home is three stories tall with about 5,000 square feet of space inside.

After hearing so much about the project, I finally decided I'd better drive to western Colorado to see the house for myself, so I visited in March 2001. The Grubers had just moved into the house, living in the downstairs while construction continued in the upper levels. I had the pleasure of being their very first overnight house guest! I included tips and photos gleaned from the project in the newest edition of Living Homes.

After hearing so much about the project, I finally decided I'd better drive to western Colorado to see the house for myself, so I visited in March 2001. The Grubers had just moved into the house, living in the downstairs while construction continued in the upper levels. I had the pleasure of being their very first overnight house guest! I included tips and photos gleaned from the project in the newest edition of Living Homes.

In June of 2001 we built our own project with this new method of slipfoming, although on a slightly smaller scale. We built a small workshop of stone beside our home, and produced a step-by-step video of the process.

-Be sure to read Dani's funny stories from the jobsite, posted at the end of this page.-

October 12, 2000

Tom,

I want to thank you so much for forwarding your book. It's been over a year since you sent it - and I've been following it closely ever since. In case you do not recall, I phoned you about the beadboard panels which you suggested for "the next generation" slipformed stone houses. Well, I am happy to say I tried it. I eventually found beadboard panels in Denver. I used 5 1/2" beadboard panels with oriented strand board glued on one side. As you can tell by the photos, the house is a large one. And you inspired me to such an extent that, with help, I even tackled turrets!

My father, (who is 73 and sports a very dry sense of humor) assures me the people doing the slipforming all died shortly afterward from the sheer effort. (This is the same guy who I showed the picture of Scott and Helen Nearing and asked him how old he thought they were. In the photo they are obviously in their 70's and 90's. Dad confidently told me he thought they were 25 and 30 - that slipforming makes everyone look like that!)

In truth, he is my biggest supporter. He's eager for a different kind of house. He mixed almost all of the mortar for me as I placed the rocks and hauled the mortar with coffee cans. (Just goes to show that where there's a will. . . .) After my muscles became accustomed to the weight of the coffee cans, and we got higher, I graduated to a mop bucket for the cement. Filling it half full and making many, many, many trips back and forth, I was sure glad to see the last rock!!!

Your book was fabulous. I'm pretty sure none of your audience has read it as thoroughly, nor as repetitively as I have. While it may be mundane to you - I wouldn't have minded another chapter on actually building the slipforms, complete with screw size, bracing, etc. The diagrams did a very good job - but for the female share of your readership, we like to know these things. My dad helped me get them straight (a rather intriguing process to me) and my husband also helped assemble them. I went through several packages of drill bits - but they look really nice. As you suggested, they have held up well and make excellent scaffold planks. They've worn many hats and seem to be holding up very well.

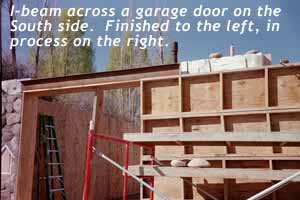

My home has gone through many changes. It started as a 24 x 64 home, then grew to a 32 x 64 two-story home. It's always easy for the people who aren't picking up the rocks to urge you to "go bigger". Showing no backbone of my own - it is now a 3-story home!

Sincerely,

Dani Gruber

Slipforming

The Next Generation

Copyright Danielle N. Gruber, February 2001

"Are you building a castle?" Sure, why not. "Are you nuts?" Sure, why not.

Forward

From the peaks of the mountains to the floors of the valleys, one can occasionally spot beautiful, simple rock homes dotting the landscape. For me, the love of a rock building was founded in a little rock barn which I yearned to remodel into a home. The rocks were cracking, and the cement was giving way, and yet the building was rich in it's simplicity. The windows would never have passed inspection. They were all very high, too high to look out of. But the light which cascaded through them, bounced off the walls and gave a glow to the floor below. Magic things happened there, I was sure. I loved that barn, and I vowed to someday build something similar for myself. But, as I researched the project, I heard from countless people warning that homes built of rock were uncomfortable. "Those homes are cool in the summer and downright cold in the winter," they'd say. So, I decided to do more research. As luck would have it, shortly thereafter, The Mother Earth News magazine had a story about a man named Tom Elpel, who was slipforming homes in Montana. Mr. Elpel had some great ideas about warming up cold rock homes. One idea was to use polystyrene beadboard insulation as an interior form. He had not tried the method, but thought it would work. I agreed and gave it a try.

Slipforming using the beadboard panels was a terrific idea. Tom Elpel's ground work in traditional slipforming was clear, concise, and very helpful. I say honestly, I could not have completed the slipformed portion of my home had it not been for him and his dedication toward documenting the process. Today, I have a home that is beautiful, warm and energy efficient, and it contains my pride at having played a part in its building process, along with my father, who graciously mixed virtually all of the cement in a $200 mixer for me. It is with thanks and gratitude to Tom and his family, and my father and my family, that I am documenting my process to help pave the road a little farther for the next generation of slipforming.

The Process

The first step, for me, was to read Mr. Elpel's book, Living Homes, and the Reader's Digest Back to the Basics. These books contain clearly how to begin construction of the most important part of the slipforming process, the slipforms themselves. I built my slipforms exactly as Elpel suggested, with two additional implements: a large clamp, and a square. The clamp came in handy when the green 2 x 4's twisted and the square kept the interior, 21" boards lined up while screwing them together.

My home was 32' x 64', so I made 24 slipforms each measuring 2' x 8'. Four were for each end, and eight for each side, plus a couple of small fill-in forms. Looking back, I could have done it with less, because, on my lot using the beadboard panels, it was impossible to easily access all sides. You can start with one full wall, or even half of one wall. However, as Elpel suggests, these forms are wonderful for use as planking, and creating this amount gave me some for scaffolding planks, some to use where I was working, and more to use in preparation for the next day's work.

My home was 32' x 64', so I made 24 slipforms each measuring 2' x 8'. Four were for each end, and eight for each side, plus a couple of small fill-in forms. Looking back, I could have done it with less, because, on my lot using the beadboard panels, it was impossible to easily access all sides. You can start with one full wall, or even half of one wall. However, as Elpel suggests, these forms are wonderful for use as planking, and creating this amount gave me some for scaffolding planks, some to use where I was working, and more to use in preparation for the next day's work.

Slipforms completed, I began searching for the beadboard panels. Mr. Elpel gave me a reference to a company in Montana, but the shipping was beyond my hopes. They referred me to a company in Denver, Colorado called Advanced Foam Plastics. While their product had not been used in this application to their knowledge, they offered a product which had traditionally been used for roofing insulation and is more readily available everywhere. It was 5 1/2" of polystyrene attached to 1/2" of oriented strand board (OSB). It is a very strong, very efficient board which is often used on roofing. They suggested it might work. The nice thing is that the panels can be built at any height from the standard 8' height up to 12'. I wanted 9' ceilings, so that is what I ordered.

Slipforming using beadboard panels is similar to traditional slipforming. The footings are built the same, except extra width is necessary for the beadboard panels. Since the floor inside this home had not been poured, I elevated the panels by 2 inches, using a recycled 2"x 10" wooden plank (the same I had used to form the footings) underneath them. Pulling the 2 x 10's out afterwards was difficult. If I built this same home over again, I would order the panels long enough to compensate for the future floor, and place them directly on the footing.

The cement and rock portion of the wall is 9" thick, and the insulated panels add another 6", so the total wall is 15" wide. That 15" wall needs an additional 4" for the slipform on the outside, and an additional 4" ledge for the beadboard panels on the inside. This brings the total width of the footing to 23". I opted to add an additional 1" to make my measurements an even two foot. Giving yourself an extra inch costs little in concrete, but is wonderful in the event any of your forms slip.

My home was built into a hillside. The back wall was back-filled so rock work was not necessary. The front of the home was resting on the slope, so I made my footings 3 feet wide along the leading edge. Since my home is sitting on a 40' vein of river rocks, I poured a footer 10" thick and used 6 one-half inch rebar runners along the 2' sides. I increased it to 8 one-half inch rebar runners along the front.

Inserting the vertical rebar into the footer

A confusing aspect was how to insert the 10' vertical rebar into the cement, leaving it 9' or higher, swaying in the wind. If you insert the long vertical rebar runners into the cement as it cures, and the rebar wobbles, even a little, you have compromised the strength of the attachment into the footer. Many people suggested cutting the rebar into two foot increments as we poured the slipformed walls. But, because the rebar temporarily supported the panels, keeping them from falling over, I wanted to keep the rebar as high as possible.

Elpel mentioned that in the past he had driven the vertical rebar through the fresh concrete of the footings into the ground beneath, but later learned that this allowed rust to creep up the rebar and compromise the strength of the connection between the footing and the wall. To avoid this, we inserted six-inch long, 1/2" PVC pieces into the cement every two feet immediately after the footers had been poured. The PVC held tight, and later, after the concrete had cured sufficiently, we hammered the rebar into those PVC pieces. The fit was very tight, and allowed no wobbling of the rebar within the hole. Of course, the rebar above the hole was able to sway, but it was held tight into the footing and allowed no seams along the vertical rebar. While this 9' of rebar was awkward, the most important benefit to leaving it that length was the rebar acted as a vertical brace for the beadboard panels. The panels leaned on the rebar. While this might not work in high wind areas, it helped to temporarily support the panels until we secured them in place.

The first beadboard panels

The first beadboard panels

The first panels I put up were the corner pieces. I am a strong woman, and managed to get the first corner up by myself, but it took the patience of Job, and would have been significantly easier with 2 or 3 people. Anyone who saw me trying to do it alone would have thought I was a nut, and might have been right. I put the 9' x 4' panel, OSB board side toward my back and piggy-backed it over to the corner, where I had set out a couple of 2 x 4's to brace it once I got there. Carefully, I backed up and set the edge of the panel in place, then reached for my 2 x 4's which were within arms reach, and braced the OSB board side of the panel. With one person on a windy day, this would have been impossible, and would have resulted in the panels falling, or creating a kite-like atmosphere while you try to piggy back it. Unless you are really head strong, I would recommend 2 people.

The vertical rebar on the other side was very helpful, and I was glad I had not cut it off. It literally held the first panel in place while I ran to get the next one. Getting the first two corner panels in place was tricky, especially since it was critical to get them square.

The space between the beadboard panel and my exterior slipform was 9". Spacers cut to this length made tightening the forms much easier. One caution: If you tighten the forms too tight, the spacers protrude into the beadboard. This makes getting them out while you are pouring concrete difficult. It also makes positioning of the rocks difficult. Put spacers in your forms, but my advice would be to keep them "girl-tight," not "man-tight."

At this point, with the vertical and horizontal rebar in place, and with the first bead board panel up, I set the remaining panels in place. With scrap 2" x 10"s, I put a 45 degree cut on each side and pre-drilled 3 holes on each side of it to make screwing it into the OSB easier. This gave me a wedge which I could then screw into the corner, holding the corner at an exact 90 degrees. I used a square, which to the horror of my male helpers, I called the "L." Once the two panels were up and square, I screwed the wedges into the corners. By the fourth corner, my father had thought up an easier way to accomplish the same end. Get a relatively large piece of scrap lumber, maybe 3 - 4 feet wide and long. Make sure it has a square edge on two corners of it, then screw a 2 x 4, level horizontally on each side of the panels, about half-way. Position the plank on top of the two ledges you created and screw your plank into the ledges. This accomplishes a nice tight corner which will not sag or change over the time necessary to complete your home. It seconds as a make-shift shelf to keep small tools.

The pieces adjoining the corners are easily placed. It helps to have scrap lumber around. Scrap pieces roughly 4" x 7" were wonderful to screw evenly across the joints between one panel and the next. Three or four of these scraps make the seams almost unnoticeable.

Wire-reinforcing

Wire-reinforcing

With rebar and spacers in place, and the first beadboard panels in place, you are ready to wire-tie the slipforms to the panels. This is an important step because too many wires in the slipform make it difficult to set rocks in place. I found that I needed about four sets of wires: two near the bottom, two near the two-foot level of the slipform at about 1' and 3' along the beadboard panel. Pre-drilling holes through the OSB board on the panels made the job easy. This job is possible for one person, but is much easier with two. It is so easy, that I had one of my kids yell when my tie wire had popped through the insulation. From there, I could pull it through and insert it into the slipform as needed. But occasionally, as you are pushing the wire through the OSB board and into the beadboard, the wire does not make a straight route and winds itself into the beadboard, never to appear on the other side. This is why it is easier to have someone on the other side. Once I looped the wire around the rebar, then through the slipform, I tightened it with a common nail. The nail anchors the beadboard to the cement.

One visitor suggested that I use the slipforms on both sides of my wall, which sounded so intelligent that I had to try it. The interior slipforms were placed right over the OSB board on the panels. What I did not foresee was the difficulty of fastening the wire ties this way. If you forego the interior slipform, the panels are strong enough, and the wire tying is easy. But with an additional slipform on the interior, the benefit of the wire tying is lost because you need to cut the wire to remove the slip-form. First, you do not need the slipforms on the inside of your wall. The panels are strong enough. But secondly, when you wire tie to the panels, you do not need to cut the wire. Both ends of the wire are fed through the panel leaving no tie on the interior wall. This is good because when you apply your interior treatment, in our case, drywall, there was no need to remove the wire ties. We did try the slipforms on both sides, but wire tying the walls then had to go completely through both sets of slipforms. Removing them meant cutting the wire. This left no remaining tie to secure the panels to the concrete. With our method, if the panels should ever come free of the cement, they will never fall off the wall, because the wire ties holds them in place.

Anytime you trek into new frontiers, there are ideas which look logical on paper, but simply are not effective. Using slipforms on both the interior and exterior proved to be one such idea. Another suggestion was gluing the insulation to the wall later. With much thought and a couple of phone calls, this concept was thrown out too. Without tying the panels into the wall, the weight of the drywall might eventually them away from the cement. One day, sitting in your living room, your whole wall might fall on top of you. We avoided this possibility, but I bring it up because anyone building a new home gets lots of advice and some of it is incredibly tempting to try.

Incidentally, I telephoned the beadboard panel company to ask if wire tying would be necessary. They could not insure the bond between the cement and the panel over time. Weight and gravity, they thought, might make the panel eventually separate from the cement without wire ties, so I opted to put them in. (A note from Tom: We are now recommending to simply drill shallow holes into the beadboard such that the concrete fills the voids and grips the panels like little fingers.) A bonus to the wire ties, is that, if you drywall, you can attach the drywall directly to the panel right over the wire. No wall preparation is necessary. A cement worker who looked at the inside of my home, insisted that we would need to fir out each panel before applying drywall, or the drywall would be a headache. I'm happy to say he was wrong. I've never done an easier drywall job. The panel, up toward the top, was not exactly level, but the slight deviance was minimal and with paint and drywall, it is almost impossible to see.

Incidentally, I telephoned the beadboard panel company to ask if wire tying would be necessary. They could not insure the bond between the cement and the panel over time. Weight and gravity, they thought, might make the panel eventually separate from the cement without wire ties, so I opted to put them in. (A note from Tom: We are now recommending to simply drill shallow holes into the beadboard such that the concrete fills the voids and grips the panels like little fingers.) A bonus to the wire ties, is that, if you drywall, you can attach the drywall directly to the panel right over the wire. No wall preparation is necessary. A cement worker who looked at the inside of my home, insisted that we would need to fir out each panel before applying drywall, or the drywall would be a headache. I'm happy to say he was wrong. I've never done an easier drywall job. The panel, up toward the top, was not exactly level, but the slight deviance was minimal and with paint and drywall, it is almost impossible to see.

Protecting the panels in wet weather

Leaving the bare OSB board out over the first winter, with no roof to protect it, scared me. A friend of mine, who is quite knowledgeable about wood, told me to paint the OSB board on each panel with a coating of half turpentine, half boiled linseed oil. This treatment waterproofs the panels sufficiently, that the OSB board did not show disintegration over the winter. Living in the Rocky Mountains, that was a testament to this treatment.

The beadboard has a flexibility which is both an asset and a drawback. It is important to keep a level close by and check the wall often. When you are going up 2' at a time, the upper level of the wall can sag out of level. It is easy to return it to level if you catch it before the concrete has been poured, but impossible if you don't catch it before the concrete cures. In two corners, toward the top, the panels began to sag a little. Since it was maybe an inch out of square, we did not lose sleep over it, and it covered easily with drywall, but it would drive a perfectionist crazy, and unnecessarily, I believe.

Removal of forms

Removal of forms

It was my experience, that in the fall, with moderate temperatures, the concrete and rock combination set up sufficiently in 5 hours. At that time, we carefully removed the forms and chipped out what cement was not desired, then left the cement alone to continue to cure overnight. A couple of times we were not able to chip off the cement until the next day, and it was much more difficult. In one section, we left it until the following night, and, in the dark, with bugs and lights, we hammered the concrete out. Sparks were flying from the hammer and the chisels, and we vowed never to do that again. The wall was no worse for the wear, but removing the cement was almost impossible.

The system we found most workable was to start at about 9:00 in the morning. My 73 year old father agreed to help me by mixing the cement in the electric mixer. (Tom Elpel said you could buy these mixers for a couple of hundred dollars. That's exactly what we paid and the mixer is still working fine after mixing almost all the cement in our large home. ) My dad would mix the cement and pour it into a wheelbarrow where I would scoop it up in coffee cans and carry it to the wall where it was easy to control and pour. Men came along and thought it would be so much easier to carry five-gallon buckets of cement, but, as I suspected, they all had dental appointments after a couple of hours.

I knew I couldn't afford to get hurt, and a coffee can of cement is not that heavy. The pace was easy to keep up, and after a couple of weeks, I got strong enough that I graduated to mop buckets, filled half-way. For three hours every morning, for three months, my dad mixed cement, and I carried it in either coffee cans or mop buckets. At noon, when the heat was unbearable, we would quit, eat, nap and recuperate. Occasionally, I would take the truck and go get more rocks and unload them. Often, I would prepare the next days forms during the afternoon, so that the next morning, we were set to go. I will add, it is amazingly tempting to try to carry more cement. My husband came up to help one day and filled the mop bucket to the top because he did not want to make two trips to the mixer. When I went to lift that bucket, it was heavy and hurt my shoulder. I was nursing that shoulder for 3 weeks. Better to make 100 trips and not be hurt than 1 trip and knock yourself out of play.

Lots of people came to visit the site. Most tried to find a more efficient way to get the concrete to the wall. I have come to believe that my pace, while slow, was perfect. By 5:00, when the forms were removed, I was happy to be chipping a reduced amount. My forms never broke. The two times I tried to hurry, I regretted it. One was on the back wall where we poured cement from a cement truck with no rocks in it. My bracing slipped and the weight of the wall pushed out the cement. Luckily, that part of the house was going to be backfilled. But the extra time to straighten the wall was not "efficient." I would have been better off to spend the extra time and not lose ground. The lesson remains, if you have patience, you won't be as likely to hurt yourself, you'll be more apt to finish the project, and with the beadboard, you are already doing two or three jobs in one since you are doing your exterior siding (rock) the structural wall (cement), and the insulation (the beadboard) and it's all ready to apply drywall to the OSB board.

Lots of people came to visit the site. Most tried to find a more efficient way to get the concrete to the wall. I have come to believe that my pace, while slow, was perfect. By 5:00, when the forms were removed, I was happy to be chipping a reduced amount. My forms never broke. The two times I tried to hurry, I regretted it. One was on the back wall where we poured cement from a cement truck with no rocks in it. My bracing slipped and the weight of the wall pushed out the cement. Luckily, that part of the house was going to be backfilled. But the extra time to straighten the wall was not "efficient." I would have been better off to spend the extra time and not lose ground. The lesson remains, if you have patience, you won't be as likely to hurt yourself, you'll be more apt to finish the project, and with the beadboard, you are already doing two or three jobs in one since you are doing your exterior siding (rock) the structural wall (cement), and the insulation (the beadboard) and it's all ready to apply drywall to the OSB board.

Filling the holes and gaps between levels

When the first level of slipforms is removed and the cement is cleaned out from between the rocks, you have a very clean looking wall. Setting the second set of forms one level higher leaves gaps and holes through which the new cement escapes and runs down the wall you just spent hours cleaning. This happened to me and plugging these holes was nearly impossible with wet cement pushing out the plugs. After some experimenting, I discovered that I could break off chunks of scrap beadboard insulation slightly bigger than the holes and wedge those scraps into the holes to prevent the new cement from escaping. It also did a much better job of preventing drips and streaks. It is not fool proof, but reduced the cleaning work substantially. Later, after the concrete has set up and the form is removed, the insulation plugs are easily removed and saved for the next level of holes and gaps.

Windows and doors

Windows and doors

The windows were purchased at a local discount window outlet earlier than we began building. Shopping for the windows first, is a great way to save a lot of money. When you have an oddly shaped window hole, the stores see dollar signs as you walk inside. But, purchasing the windows long before the building began, I was able to take advantage of top-of-the line windows at reduced prices, simply because I could use a 41" x 63" window. Tom Elpel clearly describes how to construct your window frames. Putting them into the wet cement, wedged between the slipforms and the panels, was more of a challenge.

To save money, I recycled the 2 x 10" lumber we used to form the footings. It was rough-cut lumber from a local company, so it was a full 2 x 10 inches. Since the cement part of my wall was only 9", I had to cut a ledge into the beadboard so the window frame would fit. This worked nicely because it helped hold the window frame in place. I hammered 30-40 nails and screws into the bottom of my window frame, then, when we approached the mark on the beadboard, we set the window into place and tapped it into level.

Careful measurement is necessary when the windows holes are cut into the beadboard. I left over-lapping beadboard around each edge so that when the window was placed inside, the insulation would come to the edges of the window and not the edges of the frame.

Reflections on House Plans

In my humble opinion, not enough people think about how they really live. Here's the lazy woman's guide to building a castle: Forget the view for a minute and start the plan backwards with driving up in your car. Your garage needs to be wide enough that everyone in it can open their doors and still have enough room to move. If you buy groceries - you need your kitchen close to your car. It makes unloading the car a much easier task. You need your dining room close to your kitchen for the same reason: carrying food is an accident waiting to happen and any respectable lazy person hates cleaning up food on the floor. So, now you've got the garage and the dining room close to the kitchen. You'll like that for a long time. I promise!

Also, anticipate accidents like broken legs and imagine having to urgently use the bathroom in that condition. For that reason, and because respectable lazy people don't like cleaning muddy footprints across their floor toward a far-off bathroom, I have a bathroom next to the garage and I have never regretted it. I would advise building everything to handicapped standards because 1) you could be run over by a truck tomorrow and you'd be ticked if you couldn't get around in your own house, and 2) you might be financially broke after getting run over by said truck and need to sell the place. Rich people who want to buy your house are getting old and so are you. You diminish your resalable audience if you refuse to make the doors a teensy bit wider to accommodate walkers, wheelchairs, adjustable beds, the Tonka Toys of the elderly.

Lastly, I would (and did) put a bedroom on the ground level with the garage/kitchen/dining area. It's made having guests of any age a delight instead of a nightmare.

Also, you won't find this in a home plan book - but make your kitchen bigger than you would have, and provide people a place to sit and kibitz. They will anyway! And if you have a tiny kitchen, you'll want to kill them for clogging your space. I made my kitchen large and haven't regretted it either. We've danced in there while making dinner and that's pretty rich, too! If you remember, there is a counter where I can allow people to sit while keeping me company in the kitchen. In practice, they have done exactly that and I can hand them peppers to chop and they feel included and loved. It's, as Martha Stewart would say, "a good thing."

Lastly, always have a tiny, run-down, dilapidated shed nearby, even if you don't need one. (We use the old goat shed for this purpose.) It allows you to show unappreciative guests where they can stay next time they visit. : ) I know, you didn't want to know that...

Interesting Advice And Questions From Bystanders

As overheard by me, from my father. "Oh yeah, she thinks she's going to build a rock house. We'll see. I bet when she gets a couple of feet of rock done, she'll get smart." (Later, after there was 14' of rock across the front and sides of the house and my dad was still mixing concrete.) "By God, she never did get smart."

A mechanic: "Did you cut each rock in half before putting them into the wall?" No. But what an idea! (Not!)

A legal assistant: "So, you are going to put your framing inside these foam panels?" No, there is no framing. "Oh, so your architect thought this up?" No, I couldn't afford the architect. "What! No framing!" This dear friend brought her engineer father to save me from myself. I told him about Tom Elpel's book , and about the elderly Nearings and their experience. He walked around the site a long time and was silent. He went home and was silent all afternoon. Finally, at dinner, notwithstanding the conversation, he blurted out, "I don't see why it won't work!" (And, no, there is no framing.)

A legal assistant: "So, you are going to put your framing inside these foam panels?" No, there is no framing. "Oh, so your architect thought this up?" No, I couldn't afford the architect. "What! No framing!" This dear friend brought her engineer father to save me from myself. I told him about Tom Elpel's book , and about the elderly Nearings and their experience. He walked around the site a long time and was silent. He went home and was silent all afternoon. Finally, at dinner, notwithstanding the conversation, he blurted out, "I don't see why it won't work!" (And, no, there is no framing.)

An attorney: "Are those real rocks?" My response: "I think so, but gee, I didn't look THAT close."

Same attorney: "So, you ordered those rocks and then put them together in that pattern?" (This same attorney protested a gravel pit consisting of the very same rocks I used which is less than 50 yards from my house. Why, in the world, would I import rocks when I am stumbling over hundreds, if not thousands of them to get to and from my home? "Oh."

A different attorney, sneeringly, "So, you're building with rocks and cement. . .how nice. . . .Will it be one story or two?" I don't know, I replied. "What!!! You've started it and you don't know!!!" Not yet, I answered. Then they exchanged silent glances which said, 'See why we need building codes here!' Later, this same attorney jumped out of his expensive SUV and gave me a Japanese welcome! "You've built a castle!" he said. "I cannot believe it!"

A different attorney, sneeringly, "So, you're building with rocks and cement. . .how nice. . . .Will it be one story or two?" I don't know, I replied. "What!!! You've started it and you don't know!!!" Not yet, I answered. Then they exchanged silent glances which said, 'See why we need building codes here!' Later, this same attorney jumped out of his expensive SUV and gave me a Japanese welcome! "You've built a castle!" he said. "I cannot believe it!"

A Greek neighbor who refuses to believe that a woman could do this: "Who is building this house?" I am. "No really, who is building this house?" Well, technically, my dad is helping me. "Oh, so you won't tell me. . . ." Then he jumped into his car and roared off. Later, I hired a terrific carpenter and framer to help above the 9' level. But the entire rock portion of the home was, in fact, built by my father and me and occasionally a friend or two who happened by at the wrong time.

By my father: "I'm quitting and going to work for your mother. The pay is the same and the benefits are better." My mom runs a gift shop. Both of us pay nothing, but her pay included hot coffee. Mine was all the pop he could drink. And not the good name brand kind either.

"Darn it all to heck!" Overheard by a carpenter after working with me for several months. We had Bad Word Baseball in effect. Three bad words and you had to bring donuts the next day. This kept their filthy language at a minimum so I did not take it home to my innocent children. Evidently it was working!

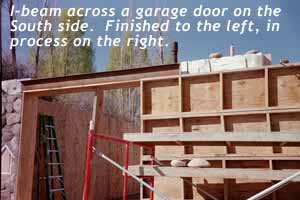

250 miles away: By a carpenter, at a bar to my husband's brother: "Man, there is this lady building this rock house in a small town where I live. The whole thing is going to fall down. I snuck up there and walked around. The cement is crumbling already. You can see it laying on the ground where it is falling off the wall. She's got no headers over her windows and the whole thing is made with foam. I sure hate to see them fail. They've put a lot of work and money into it so far. (This story caused panic among my in-laws who were almost all afraid to bring it to my attention. Finally, one e-mailed my husband and whispered his concern. The "crumbling concrete" was the cement that I had scraped off from in between the rocks. No worry. The headers for the windows? We weren't even that high yet. Of course, we put U-channel metal headers over each window and door that were structurally engineered for correct size. The foam, well, it was Elpel's idea.) Later, the same carpenter came back. After he had walked through the dried-in home, he was eating his words admitting that he'd never seen a home built like this before, but was impressed.

My father: "If I'd have known what you were building, and that you were going to stick it through, I'd have quit earlier!"

Check out Living Homes: Stone Masonry, Log, and Strawbale Construction.

|

DirtCheapBuilder.com

DirtCheapBuilder.com

The first beadboard panels

The first beadboard panels Wire-reinforcing

Wire-reinforcing Incidentally, I telephoned the beadboard panel company to ask if wire tying would be necessary. They could not insure the bond between the cement and the panel over time. Weight and gravity, they thought, might make the panel eventually separate from the cement without wire ties, so I opted to put them in. (A note from Tom: We are now recommending to simply drill shallow holes into the beadboard such that the concrete fills the voids and grips the panels like little fingers.) A bonus to the wire ties, is that, if you drywall, you can attach the drywall directly to the panel right over the wire. No wall preparation is necessary. A cement worker who looked at the inside of my home, insisted that we would need to fir out each panel before applying drywall, or the drywall would be a headache. I'm happy to say he was wrong. I've never done an easier drywall job. The panel, up toward the top, was not exactly level, but the slight deviance was minimal and with paint and drywall, it is almost impossible to see.

Incidentally, I telephoned the beadboard panel company to ask if wire tying would be necessary. They could not insure the bond between the cement and the panel over time. Weight and gravity, they thought, might make the panel eventually separate from the cement without wire ties, so I opted to put them in. (A note from Tom: We are now recommending to simply drill shallow holes into the beadboard such that the concrete fills the voids and grips the panels like little fingers.) A bonus to the wire ties, is that, if you drywall, you can attach the drywall directly to the panel right over the wire. No wall preparation is necessary. A cement worker who looked at the inside of my home, insisted that we would need to fir out each panel before applying drywall, or the drywall would be a headache. I'm happy to say he was wrong. I've never done an easier drywall job. The panel, up toward the top, was not exactly level, but the slight deviance was minimal and with paint and drywall, it is almost impossible to see.  Removal of forms

Removal of forms Lots of people came to visit the site. Most tried to find a more efficient way to get the concrete to the wall. I have come to believe that my pace, while slow, was perfect. By 5:00, when the forms were removed, I was happy to be chipping a reduced amount. My forms never broke. The two times I tried to hurry, I regretted it. One was on the back wall where we poured cement from a cement truck with no rocks in it. My bracing slipped and the weight of the wall pushed out the cement. Luckily, that part of the house was going to be backfilled. But the extra time to straighten the wall was not "efficient." I would have been better off to spend the extra time and not lose ground. The lesson remains, if you have patience, you won't be as likely to hurt yourself, you'll be more apt to finish the project, and with the beadboard, you are already doing two or three jobs in one since you are doing your exterior siding (rock) the structural wall (cement), and the insulation (the beadboard) and it's all ready to apply drywall to the OSB board.

Lots of people came to visit the site. Most tried to find a more efficient way to get the concrete to the wall. I have come to believe that my pace, while slow, was perfect. By 5:00, when the forms were removed, I was happy to be chipping a reduced amount. My forms never broke. The two times I tried to hurry, I regretted it. One was on the back wall where we poured cement from a cement truck with no rocks in it. My bracing slipped and the weight of the wall pushed out the cement. Luckily, that part of the house was going to be backfilled. But the extra time to straighten the wall was not "efficient." I would have been better off to spend the extra time and not lose ground. The lesson remains, if you have patience, you won't be as likely to hurt yourself, you'll be more apt to finish the project, and with the beadboard, you are already doing two or three jobs in one since you are doing your exterior siding (rock) the structural wall (cement), and the insulation (the beadboard) and it's all ready to apply drywall to the OSB board. Windows and doors

Windows and doors

A legal assistant: "So, you are going to put your framing inside these foam panels?" No, there is no framing. "Oh, so your architect thought this up?" No, I couldn't afford the architect. "What! No framing!" This dear friend brought her engineer father to save me from myself. I told him about Tom Elpel's book , and about the elderly Nearings and their experience. He walked around the site a long time and was silent. He went home and was silent all afternoon. Finally, at dinner, notwithstanding the conversation, he blurted out, "I don't see why it won't work!" (And, no, there is no framing.)

A legal assistant: "So, you are going to put your framing inside these foam panels?" No, there is no framing. "Oh, so your architect thought this up?" No, I couldn't afford the architect. "What! No framing!" This dear friend brought her engineer father to save me from myself. I told him about Tom Elpel's book , and about the elderly Nearings and their experience. He walked around the site a long time and was silent. He went home and was silent all afternoon. Finally, at dinner, notwithstanding the conversation, he blurted out, "I don't see why it won't work!" (And, no, there is no framing.) A different attorney, sneeringly, "So, you're building with rocks and cement. . .how nice. . . .Will it be one story or two?" I don't know, I replied. "What!!! You've started it and you don't know!!!" Not yet, I answered. Then they exchanged silent glances which said, 'See why we need building codes here!' Later, this same attorney jumped out of his expensive SUV and gave me a Japanese welcome! "You've built a castle!" he said. "I cannot believe it!"

A different attorney, sneeringly, "So, you're building with rocks and cement. . .how nice. . . .Will it be one story or two?" I don't know, I replied. "What!!! You've started it and you don't know!!!" Not yet, I answered. Then they exchanged silent glances which said, 'See why we need building codes here!' Later, this same attorney jumped out of his expensive SUV and gave me a Japanese welcome! "You've built a castle!" he said. "I cannot believe it!"